Acquiring more tools to get to the good stuff

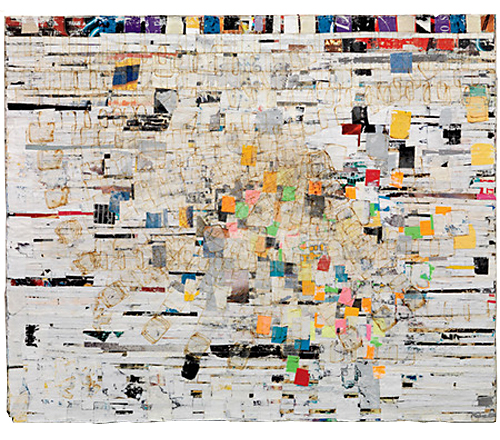

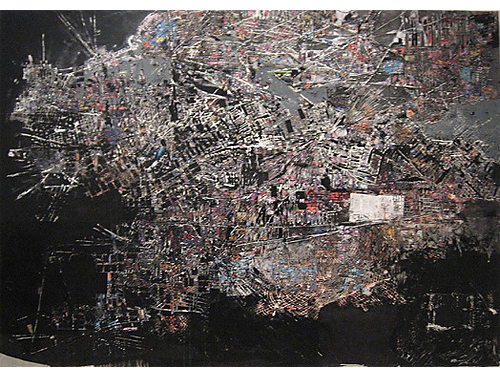

Sunday, March 5th, 2017Too often we rush through an exhibit and decide within a second or two if a work is worthy of more attention. Are we using the right language to make a judgement, or have we never acquired the tools for negotiating the visual unfamiliar in the first place? We take for granted that the eyesight most of us have been granted arrives with the same filters and “instructions†for interpretation, but the lack of an education on how to read—or at least enter—a work of art forces some of us to respond only viscerally to new work. Without some degree of  comfort with this language, we ignore art that has the potential to captivate and enrich. We don’t stop to look because of the difficulty of making judgements about how the work communicates its intentions and how original—or even unique to the artist—the piece is. By this, I mean two things.

The first are the formal elements that allow us to “diagram the sentence.†We understand the roles that nouns, verbs and prepositions play in our ability to express ideas, but many of us are clueless about the architecture of a visual sentence. Some depend on shorthand phrases, learned in an art history course or absorbed through culture, to help them navigate. Learning to understand how these are put together to construct bigger and more complicated ideas—first a sentence, then a paragraph—takes commitment, but repeated direct encounters with art can help you engage in deeper ways. Is that shape in the painting attempting to describe a three-dimensional object? How is color affecting the way I understand this piece of sculpture? Why are these two very different objects displayed side-by-side? And so on.

The second is the personal visual vocabulary that marks a piece as the work of a particular artist. Recognizing an artist’s “accent†is not just a quick way to establish what might be at play in a piece because of its connection to a particular time period or school. If you know the artist, it is also a way to establish a dialogue between any past work with which you are familiar and the new work you encounter, and that itself creates another dimension of insight. Your understanding deepens because you are not just comparing the work to all art, but drawing conclusions based on decisions that the artist has made—or not made—in the past. You can build this new responsive muscle, exercising your eyes and mind, by sharing a space—and time—with actual artwork.

I know that enlarging your vocabulary is a difficult task, but I have what might seem like a counter-intuitive suggestion. The next time you are at a museum or gallery, look for art that disrupts your assumptions or offends your sensibilities instead of work that calls out to you. Instead of rejecting it out-of-hand, spend some time with it. Your struggle to find meaning, together with the time you put into it, will reveal things that a quick walk past it never can. It might change how you conduct a subsequent visit to a museum. It will certainly have given you a new experience.